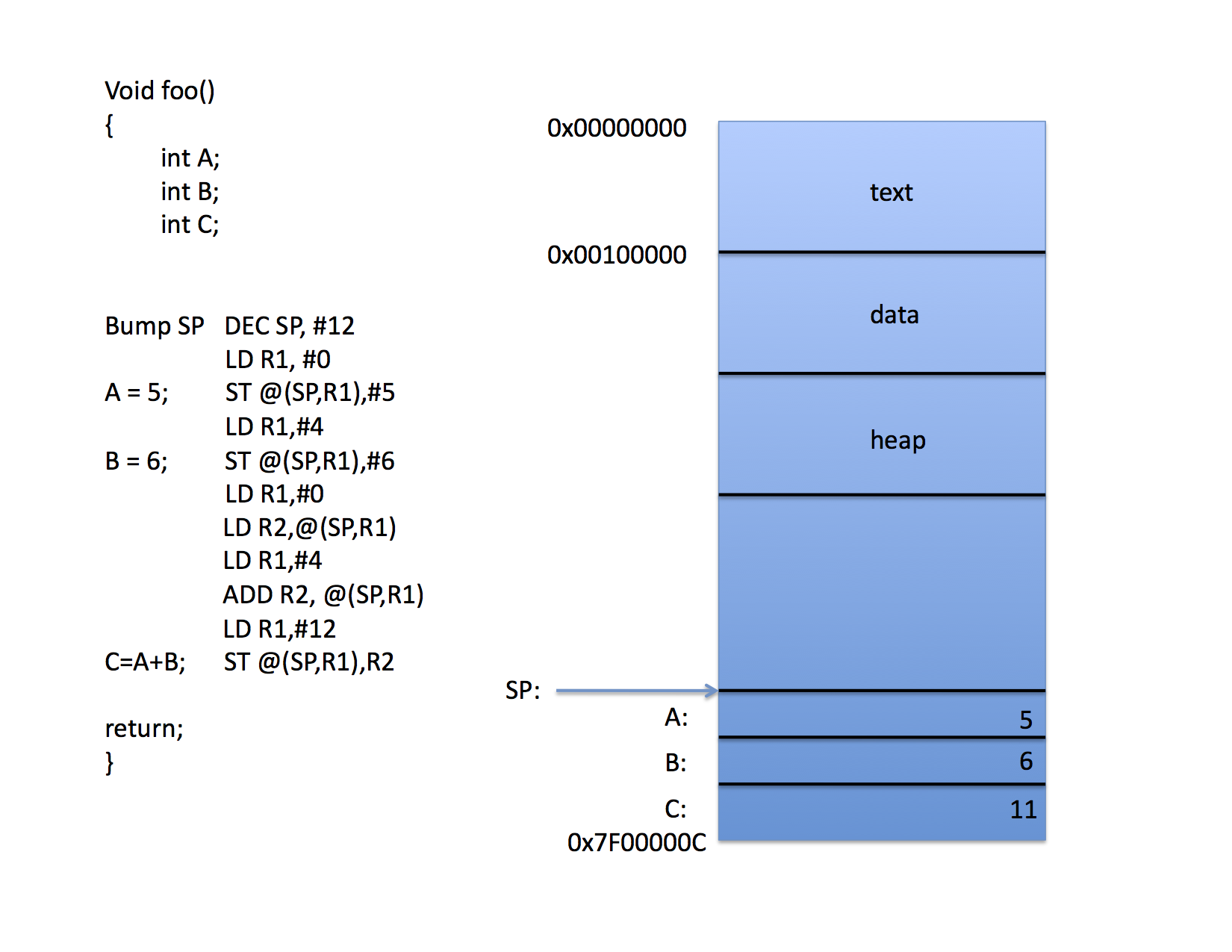

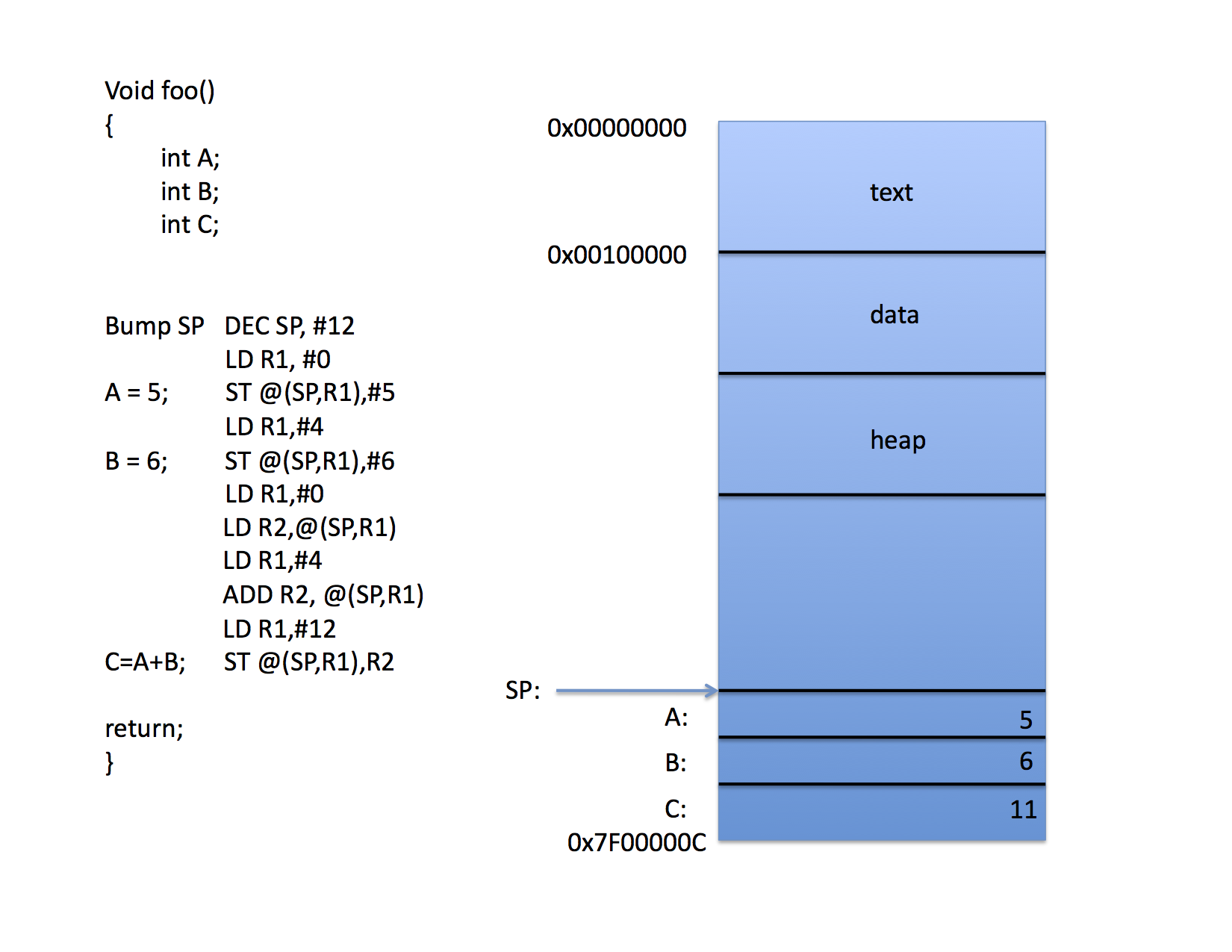

The local variables A,B, and C are all addressed via the SP register by computing a memory address by adding the contents of the SP to the contents of an offset register (R1 in the figure).

Thus, when the program is loaded into memory, the loader "knows" that the stack pointer will start at location 0x7f00000c and it tells the OS to initialize the SP with this value. The call to foo() can been compiled to pus the space for three integers onto the stack and the code accesses the variables indirectly through the SP and individual offsets for each variable.

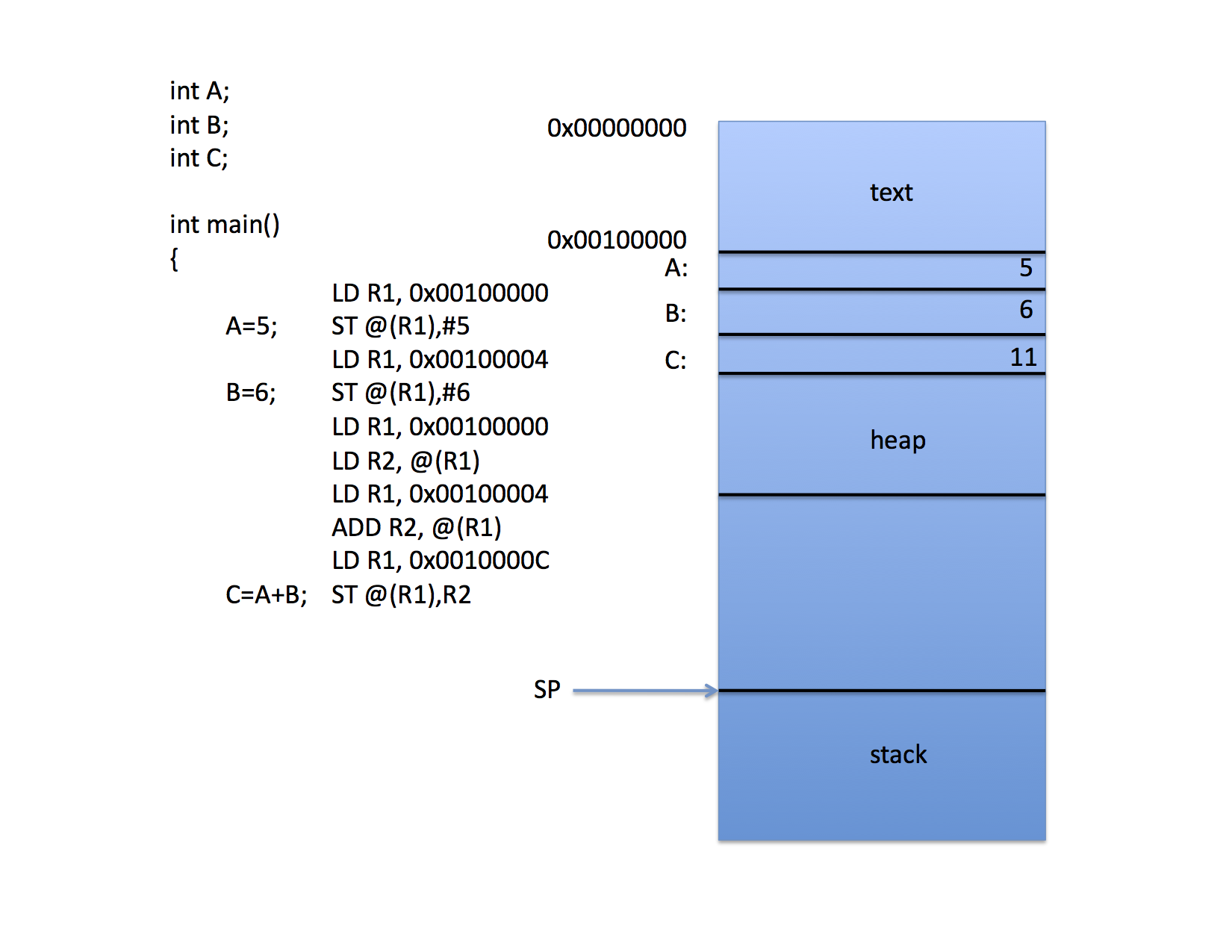

That's fine for the stack where there is always a machine register that defines the top of the stack. CPUs do not have explicit registers for the other segments in a Linux a.out process image, however. Thus, when accessing global variables, the compiler must either "burn" a register for the start of the data segment (which is costly since there aren't enough registers as it is) or it must "hard code" addresses (as in the following figure):

Again, the compiler has chosen to access memory via indirect addressing, but it does so with address constants to save registers for computation.

This work fine when

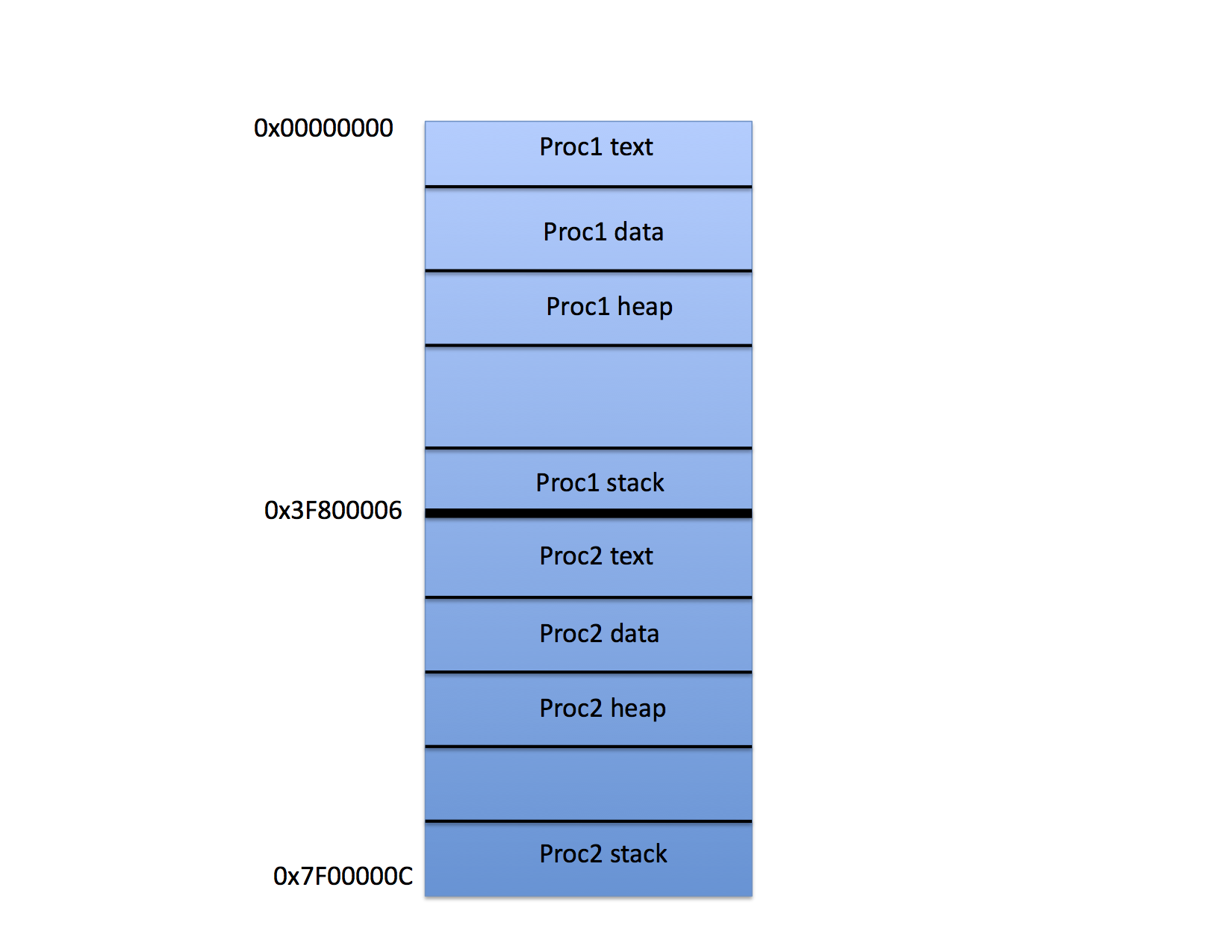

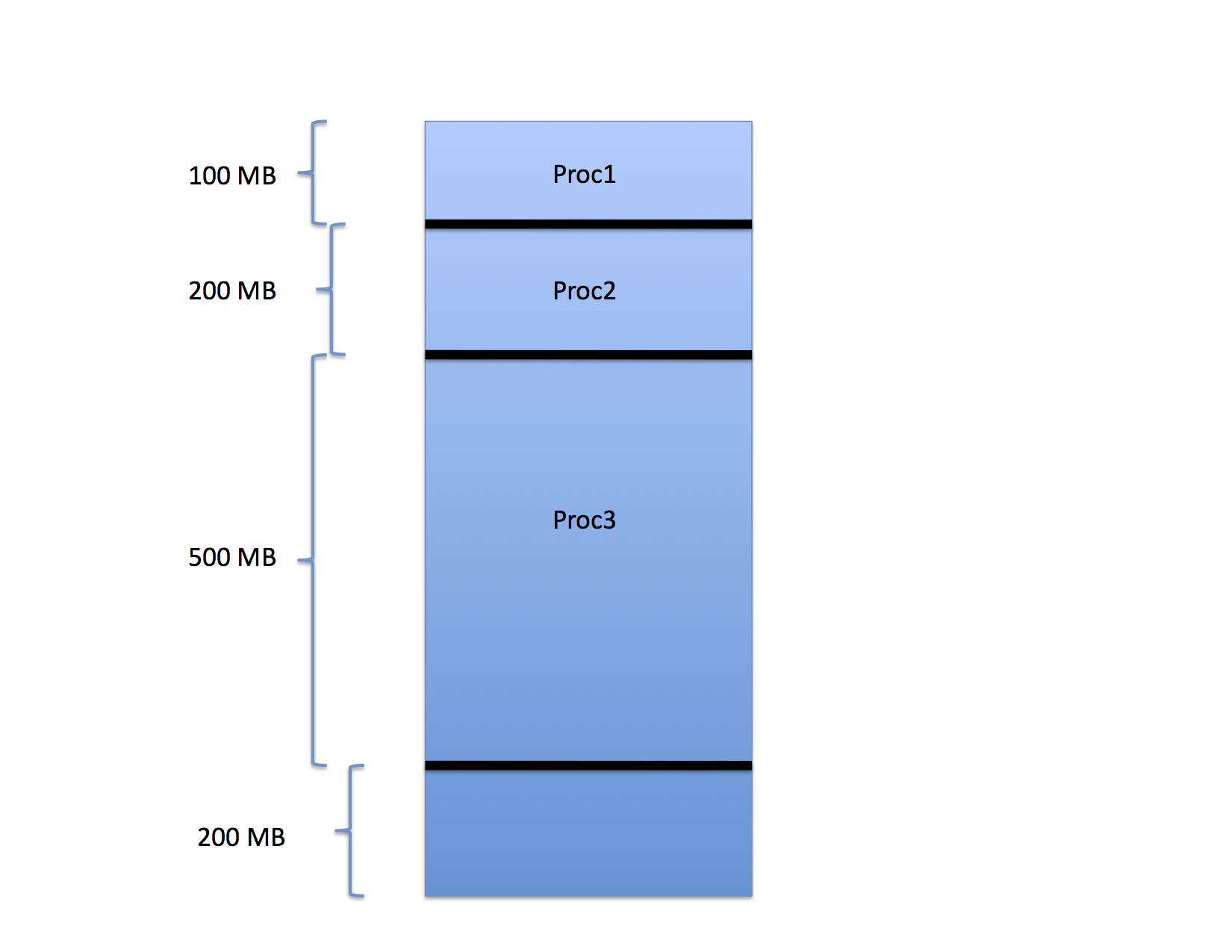

On this figure, Proc1 has been loaded into the top half of the physical memory and Proc 2 into the bottom half. Presumably the OS is prepared to switch back and forth between the two processes using time slicing and context switching.

However notice that if it is physical memory alone, the compiler must "know" where the program will be loaded so that it can adjust the address constants appropriately. The stack pointer isn't a problem, but the global variables are.

Worse, in this scenario, one program can read and update the variables belonging to the other simply by addressing the memory. For example, if Proc 1 executes the instruction sequence

LD SP, 0x7f00000Cit will suddenly be accessing the stack variables of Proc 2.

Thus the compiler uses the same address constants for every program it compiles, usually assuming that the program will be loaded at location zero. When the OS loads the program, it sets the base register to the physical address where the program should start and the CPU adds this value to every address that the process uses when it is executing.

For example, in the figure, the base register would be loaded with 0x3f800006 when Proc 2 is running. The compiler, however, would compile Proc 2 as if it were always loaded at location 0x00000000 and the CPU adds the contents of the base register to every attempt to access memory before the access takes place.

Notice that when the CPU switches to run Proc 1 it must change the base register to contain 0x00000000 so that the addresses in Proc 1 are generated correctly. When the CPU switches back to Proc 2 it must reload the correct base address into the base register at context switch time, and so on.

Notice also that it is possible, using this scheme, to switch Proc 1 and Proc 2 in memory. If, say, Proc 1 were written to disk and then Proc 2 were written to disk and then Proc 1 were read from disk, but this time into memory starting at 0x3f800006 it would run just fine as long as the base register were set to 0x3f800006 every time it runs.

The limit register is just like the base register except it indicates the largest address that the process can access. Because it isn't used to compute the address it is sometimes expressed as a length. That is, the limit register contains the maximum offset (from zero) that any address can take on.

When a process issues a request for memory, then, the address that has been generated by the compiler is first checked against the value in the limit register. If the address is larger than the limit value, the address is not allowed (and a protection fault is generated, typically). otherwise, the address is added to the value in the base register and sent to the memory subsystem of the machine.

Because these operations are done in the CPU hardware they can be implemented to run at machine speed. If the instructions necessary to change the base and limit registers are protected instructions, then only the OS can change them and processes are protected from accessing each other's memory.

This type of memory partitioning scheme is called "fixed" partitioning and it was used in some of the early mainframe computers. When the machine is configured, the administrator (or systems programmer) would set the number of partitions that the machine could use and the OS would schedule processes to use them.

In the Linux example shown above, the space between the heap (which grows toward higher memory addresses) and the stack (which grows toward lower memory addresses) is unused memory. If the text segment is loaded at the lowest address in a partition and the initial SP is set to the highest address in the partition when the process is first loaded, any space between the heap and stack boundaries is idle memory. The process may use it, but it is not available to other processes. Thus a process with a small text, data, heap, and stack still takes up a full partition even if it only uses a small fraction of the available memory space.

This problem is called fragmentation since the memory is divided into fragments (each of which is contiguous) of "used" and "unused" memory. More specifically, when the partitions are fixed in size, the term internal fragmentation is often used to indicate that the fragmentation is internal to the partitions.

It is possible, however, for the OS to choose different values dynamically as memory demand varies. Because the code is relocatable based on the base and limit registers it can vary the partition boundaries possibly reloading a program into a smaller or larger partition.

For example, when the OS boots, if it runs a single process, that process can be given all of memory. If a second process arrives to be scheduled, the OS can

For these reasons the typical implementation would give each process a maximum field length when it was created (usually based on some user input or administrator set parameters). Once a process began executing it would not change its field length. The OS would then assign a base register value when the process runs based on the other processes already running in memory.

For example, consider the three processes that have been loaded into memory as shown in the following figure.

In the figure, Proc1 occupies the first 100 MB of space in a memory that is 1GB is total size. Proc2 occupies the next 200 MB and Proc 3 occupies the 500 MB after that. The last 200 MB are free.

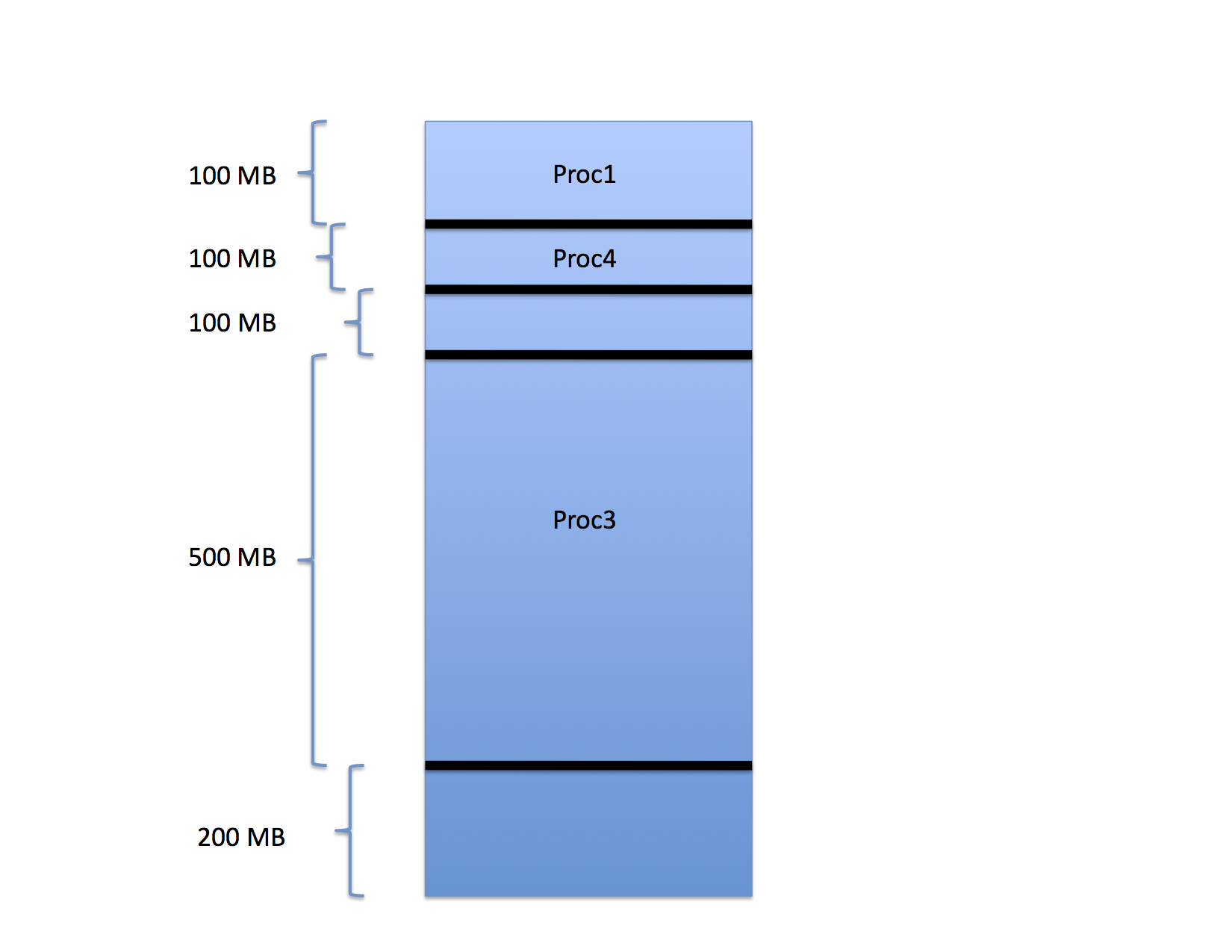

When these processes were loaded, the OS chose the base register value for each so that the processes would pack into memory in this way. That is, the base register value for the next process is the sum of the base and limit values of the one before it. If a fourth process were to arrive, the OS would schedule it to the last 200 MB of memory accordingly.

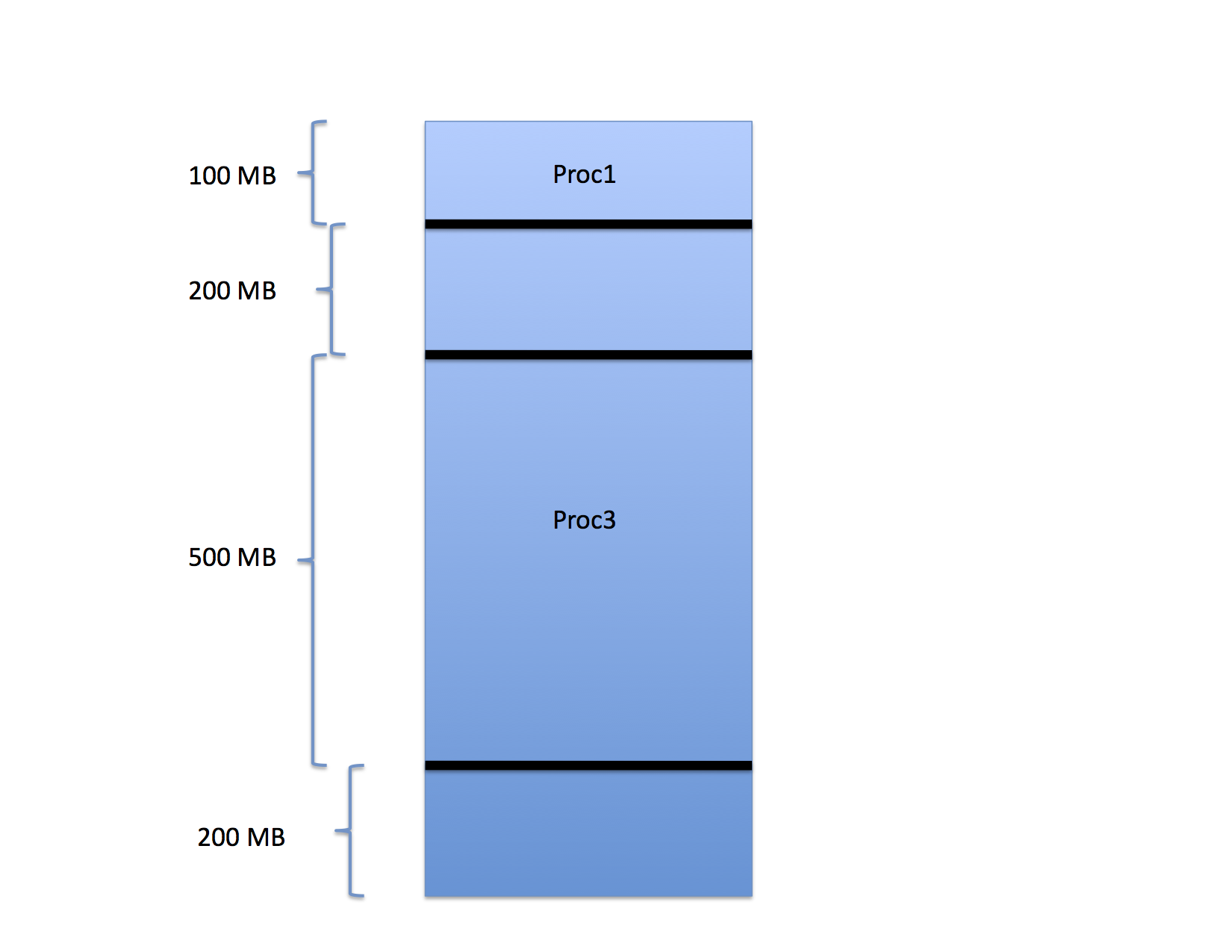

The region freed by Proc2 between Proc1 and Proc3 can now be assigned to a new process as can the free region between the end of Proc3 and the end of memory.

Notice, though, that there are 400 MB free but the largest process that can be run is only 200 MB. What happens if a 300 MB process arrives? It cannot be started even though only 60% of the memory is occupied.

This type of fragmentation is often called external fragmentation because the wasted space occurs outside of each assigned partition.

as shown for Proc4.

So far so good, but now consider what happens if the fifth process to arrive requires 75 MB. In which hole should the OS place this job? Generally, there are three options:

To swap a process out, the OS must

Similarly, to swap a process in, the OS must

Thus, as a form of slow motion "time slicing" the OS can multiplex the memory by swapping processes to disk. The disk and copy times are long compared to CPU execution speeds. Thus the interaction between the CPU process scheduler and the memory scheduler must be "tuned." The typical interaction is to allow the in-memory processes to run for some long period while others wait on disk. As the disk processes "age" their priority for memory goes up (although at a slower rate than the aging rate for processes that are waiting for CPU in a CPU timeslicing context). Eventually, when a disk process has waited long enough, an in-memory process is selected for eviction to make room for the in-coming disk process, and so on.

Notice that the first-fit, best-fit, worst-fit situation pertains to the disk as well. The backing store is usually a fixed region of disk space (larger than the size of main memory) that must be partitioned to hold process images while they are waiting to get back into memory.

Modern operating systems such as Linux use swapping (hence the term "swap space" or "swap partition" that you may have heard in conjunction with configuring a Linux system). As we will see, however, they do so in a slightly different way than we have discussed thus far.

The notion of physical memory partitioning may seem quaint by modern standards. It is efficient with respect to execution speed, however, since the base and limit register accesses are almost trivial in terms of CPU cycles lost to memory protection. So much so that specialized supercomputers like those built by Cray used this scheme for many years.

The basic idea is pretty simple. Instead of having a single base and limit register for the entire process (thereby requiring the whole process to be in contiguous memory), the CPU supports the notion of a "map" that automatically converts a relocatable address to a physical memory address. Thus, as is the case with memory partitioning, each process is compiled so that its internal addressing is relative to address 0x00000000 and the hardware maps each address to a physical memory address automatically. In the case of base and limit the mapping is an addition of the value contained in the base base register to the address to provide an address in physical memory.

For demand paging, however, the map is a table in memory that the OS sets up which tells the CPU explicitly where to find a memory reference in physical memory. The OS loads the address of this table into a special CPU register when the process is scheduled and all references to memory made by the process are subjected to the mapping operation by the CPU so that they can be translated into physical addresses.

However, to cut down on the number of entries in the table, individual address are not mapped. Rather, the memory is broken up into pages of a fixed size. All pages are the same size and, for reasons of efficiency, the size needs to be a power of 2.

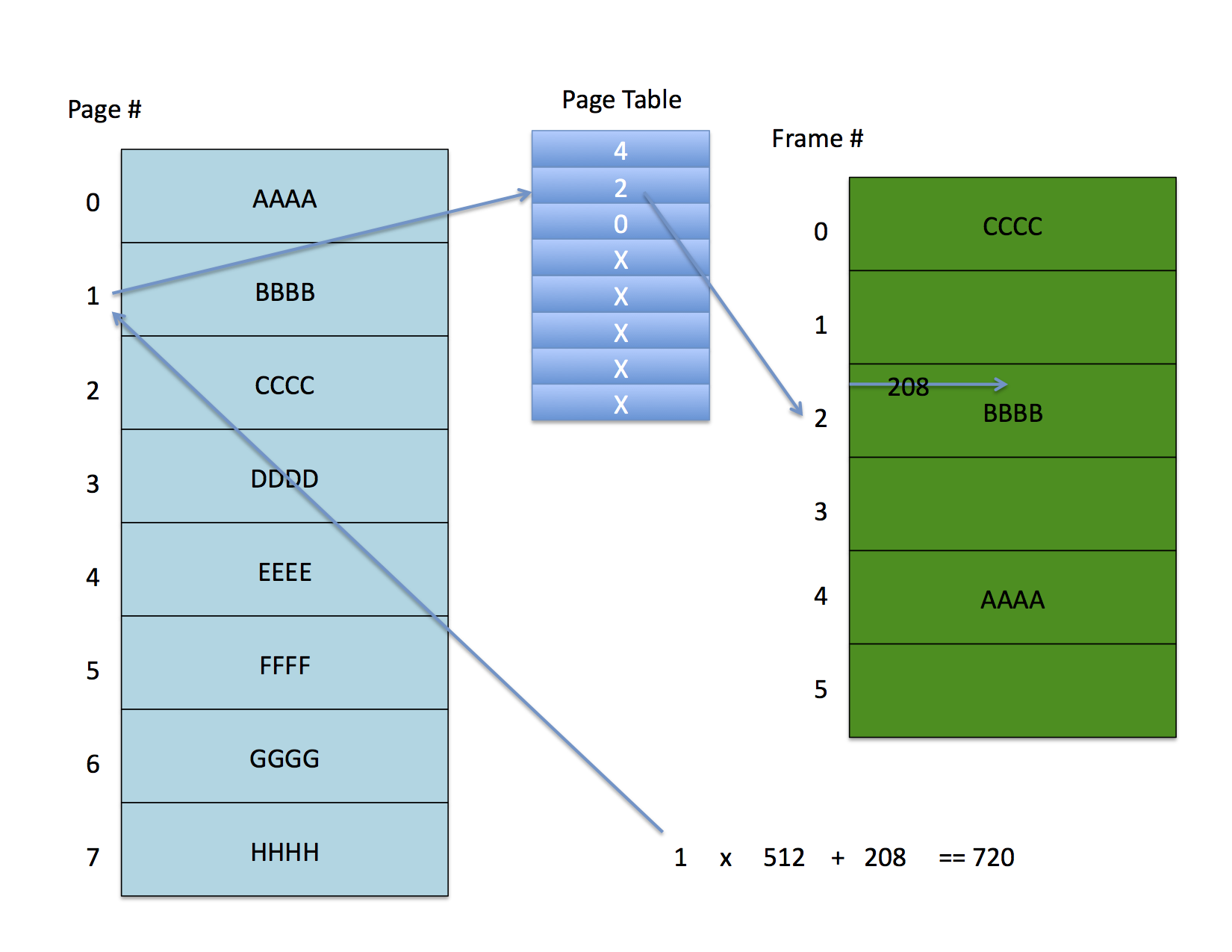

However, consider the following example address

0x000002D0This address is 720 in decimal. Let's look at it in binary, though

0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0010 1101 0000So far so good? Okay now think of it this way. Instead of it being the 720th byte in memory, imagine it to be the 208th byte in a 512 byte page that has been mapped to some physical page frame in physical memory. That is, the low-order 9 bits in the address give you an offset from the nearest 512 byte frame in the memory space. Put another way, you can think of an address as being an offset from zero or you can break it up into pages that are powers of two in size, in which case

For example, if the page size is 512 bytes, then boundary between page number and offset is defined so that the low-order offset is 9 bits since 2^9 is 512.

Page Number | Offset

|

0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 001 | 0 1101 0000

|

|

The left most 23 bits in this address give the page number which, in

this example, is 1. The offset is 0xD0 which, in decimal, is

208. Thus to compute the linear address we can multiply the page

number by the page size and add the offset:

Page Number Page Size Offset

----------------------------------

1 x 512 + 208 == 720

Why does this matter? Because it allows us to build a table that will map

pages of address space to arbitrary pages in physical memory based on page

number. An address translation requires the following steps be executed by

the CPU each time an address is referenced by a process.

Each entry in the page table actually contains more than the frame number. In particular each page table entry contains

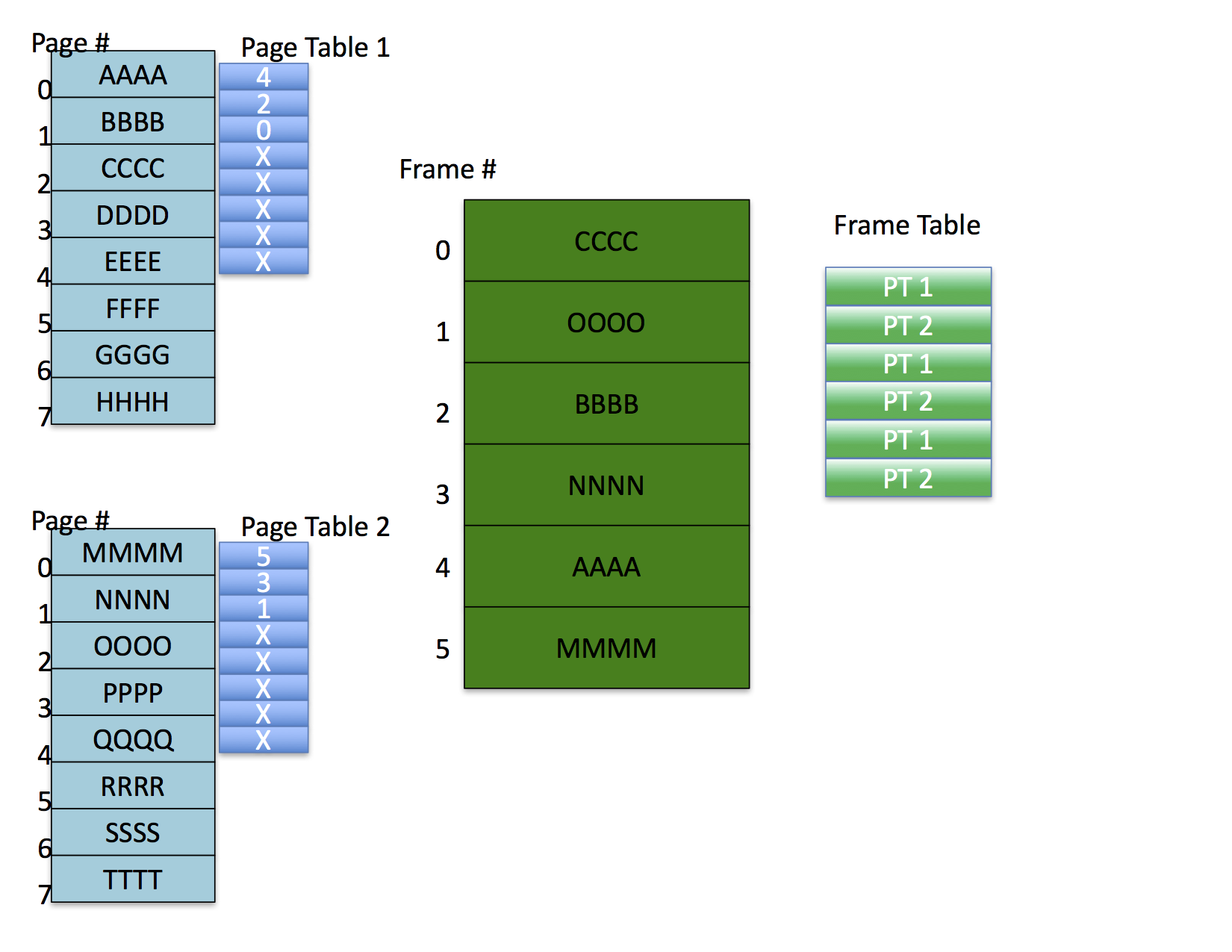

----------------------------------------------------------------- | Physical Frame # | valid | modified | referenced | protection | -----------------------------------------------------------------Ignoring these additional bits for a minute, the following figure shows a possible page mapping

The address space on the left is partially mapped to the physical memory on the right. Address 720 with a 512 byte page size indexes to the second entry (counting from zero) in the page table. This entry contains frame number 2 which, when multiplied by the page size and added to the 208 byte offset yields the physical address.

It is important to understand that this address translation is done by the CPU (or more properly by the MMU -- memory management unit) on every memory access -- it cannot be avoided. Thus as long as the OS controls the set up of the page table processes cannot access each other's memory.

Further, each process needs its own page table. It is possible for processes to share memory, however, if the same frame number is listed in each sharing process' page table. Notice also that if they were to share memory, they don't need it to have the same address in their respective memory spaces.

For example, page 7 in process 1 might refer to frame 5 which is being shared with process 2 which has it mapped to page 10. In this example, the 8th entry of process 1's page table would contain 5 and the 11th entry in process 2's page table would also contain 5 since they are both mapping frame 5.

The protection field usually contains two bits that enable four kinds of access:

For what remains, recall that the page number is an index into a table of these entries from which the frame number is recovered.

To figure out where the data resides on disk, the system maintains a second table, also indexed by page number, that contains the following entries.

------------------------------------------------- | swap device # | disk block # | swap file type | -------------------------------------------------Don't worry about the type. Just notice that what the kernel is doing here is storing the disk location where the backing store for a given page is located. Logically, these two entries are part of the sample table entry. they are typically implemented as separate tables, however, since the hardware will want pages tables to look a certain way, but backing store descriptors are completely up to the OS to define.

-------------------------------------------------- | ref count | swap device # | disk block # | PTE | --------------------------------------------------for each frame in the system. There are also some other fields that have to to with allocating and freeing frames but we won't go into the details. Suffice to say that the OS need to be able to sweep through the frames that are currently occupied in memory every once and a while and knowing where the frame is paged on memory is handy.

In summary,

Each frame table entry for memory indicates which page table entry corresponds to the mapped page in the frame.

Notice also that, in this example, the OS has allocated pages to frames such that there are no shared frames. It is possible, however, for processes to share memory under this scheme by having different pages mapped to the same frame. In this case, the frame table requires a list of page table entries for the page tables that map the frame (not shown in the figure).

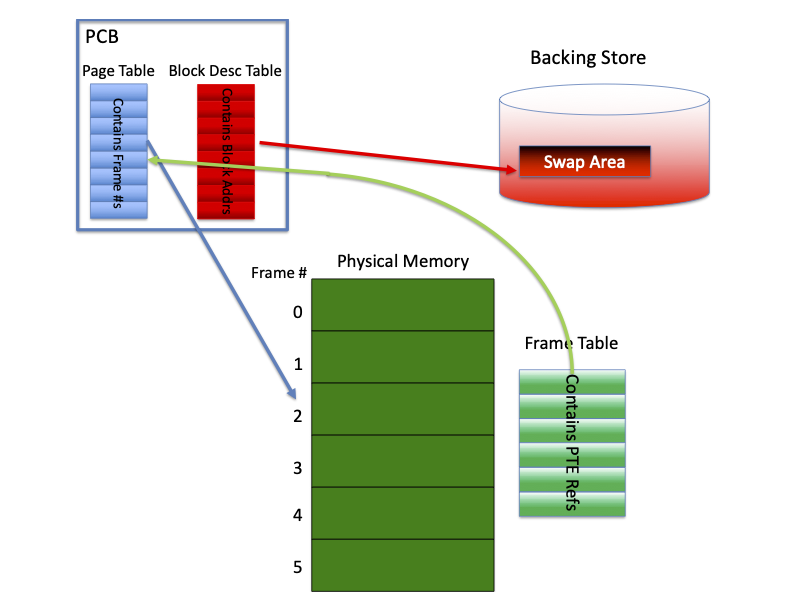

This figure shows the relationship between the per-process tables (page table

and block descriptor table), the frame table, and the swap area contained in

the backing store.

Each process has a page table and a block descriptor table that are part of

the processes kernel state. Usually this information is kept in the process'

PCB. The page table for the process contains frame numbers referring to

physical frames. The block descriptor tables contains block addresses in the

swap area for the shadow copies of pages. There is a single frame table that

contains pointers to page table entries (PTEs) for frames that are currently

allocated to pages.

Each process has a page table and a block descriptor table that are part of

the processes kernel state. Usually this information is kept in the process'

PCB. The page table for the process contains frame numbers referring to

physical frames. The block descriptor tables contains block addresses in the

swap area for the shadow copies of pages. There is a single frame table that

contains pointers to page table entries (PTEs) for frames that are currently

allocated to pages.

When the CPU does the address translation, and it goes to fetch the frame number from the page table entry, it check the valid bit. If the valid bit is clear, the CPU throws a page fault which traps into the OS. The OS must find a free frame, load the frame with the data from the address space into the frame, and restart the process at the place where the fault occurred, load the frame with the data from the address space into the frame, and restart the process at the place where the fault occurred.

The only two pieces you are missing, before understanding exactly how this works concern how frames are allocated and deallocated, and how swap space (backing store) is managed. We won't discuss these two issues in detail since they vary considerably from system to system. Each OS includes a swap space manager that can allocate and deallocate frame sized regions of disk space from the swap partition. Most OSs also maintain an internal "cache" of pages that have been used recently but are not allocated to a process. This page cache gets searched (efficiently) before the OS goes to disk to get a page.

The term "dirty" is sometimes used to refer to a page that has been modified in memory, and the modified bit is occasionally termed "the dirty bit." Notice that a dirty page is always more current than the backing store copy. Thus, to "clean" a page, the copy that is in memory must be "flushed" back to backing store, updating the backing store copy to make it consistent with the memory copy.

What would happen if the OS, when confronted with no free frames, simply chose a frame that was being used by a program, cleared the valid in the program's page table entry and allocated the frame to the new program? If the program that originally owned the frame were using it, it would immediately take a page fault (as soon as it ran again) and the OS would steal another frame. It turns out that this condition occurs (in a slightly different form) and it is called thrashing. We'll discuss that in a minute, but the remarkable thing to notice here is that the OS can simply steal frames that are in use from other programs and those programs will continue to run (albeit more slowly since they are page faulting a great deal).

What actually happens has to do with locality of page references. It turns out that a large number of studies show that program access "sets" of pages for a good long while before they move on to other "sets." The set of pages that a program is bashing through repeatedly at any given time is called the programs run set. Very few programs have run sets that include all of the pages in the program. As a result, a program will fault in a run set and then stay within that set for a period of time before transitioning to another run set. Many studies have exposed this phenomenon and almost all VM systems exploit it. The idea, then, is to try and get the OS to steal frames from running programs that are no longer part of a run set. Since they aren't part of a run set the program from which the frames are stolen will not immediately fault them back in.

Here is the deal. First, every time a reference is made to a page (with read or write) the hardware sets the referenced bit in the page table entry. Every time.

The page stealer wakes up every now and then (we'll talk about when in a minute) and looks through all of the frames in the frame table. If the referenced bit is set, the page stealer assumes that the page has been referenced since the last time it was checked and, thus, is part of some processes run set. It clears the bit and moves on. If it comes across a page that has the referenced bit clear, the page stealer assumes that the has not been referenced recently, is not part of a run set, and is eligible to be stolen.

The actual stealing algorithms are widely varied as Linux designers seem to think that the way in which pages are stolen makes a tremendous performance difference. It might, but I've never heard of page stealing as being a critical performance issue. Still one methodology that gets discussed a great deal is called the clock algorithm. Again -- there are several variants. We'll just talk about the basics.

The page stealer then maintains two "hands" -- one "hand" points to the last place the page stealer looked in the frame table when it ran last. The other "hand" points to the last place it started from. When the page stealer runs, it sweeps through the frame table between where it started last and where it ended last to see if any of the referenced bits are set.

v = 0 or ref cnt = 0 : page is free so skip it v = 1, r = 1 : page is busy. clear and skip v = 1, r = 0, m = 0 : page is clean and unreferenced. steal v = 1, r = 0, m = 1 : page is dirty and unreferenced schedule cleaning and skip

Once the page stealer has run this algorithm for all of the pages between its start point and end point, it must move these points in the frame table. it does so by changing the new start point to be the old end point (wrapping around the end of the frame table if need be) and then it walks forward some specified number of frames (again wrapping if needed) clearing the referenced bit for each frame. These are the new start and end points ("hands") for the next time it wakes up.

It is called the clock algorithm because you can think of the frame table as being circular (due to the wrap around) and because start and end pointers work their way around the circle.

Variations on this theme include "aging counters" that determine run set membership and the way in which dirty pages are handled. I'll just briefly mention two such variations, but each Linux implementation seems to have its own.

If you think about it for a minute, you can convince yourself that the clock algorithm is an attempt to implement a Least Recently Used (LRU) policy as a way of taking advantage of spatial and temporal locality. The most straight-forward way to implement LRU, though, is to use a time stamp for each reference. The cost, of course, would be in hardware since a time stamp value would need to be written in the page table entry each time a reference occurred. Some systems, however, time stamp each page's examination by the page stealer using a counter. Every time the page stealer examines a page and find it is a "stealable" state, it bumps a counter and only steals the page after a specified number of examinations.

The other variation has to do with the treatment of dirty pages. SunOS versions 2.X and 3.X (Solaris is essentially SunOS version 4.X and higher) had two low-water marks: one for stealing clean pages and a "oh oh" mode when all stealable pages would be annexed. In the first mode, when the system ran a little short of pages, it would run the clock algorithm as described. If that didn't free enough pages, or if the free page count got really low, it would block the owners of dirty pages while they were being cleaned to try and get more usable on the free list before things got hot again. Usually, if the kernel found itself this short-handed, the system would thrash.

vmstat (after consulting the man page for details on its

function). Among other valuable pieces of information, it typically includes

paging rates. No Linux systems that I know of automatically throttle process

creations as a result of paging activity, but the information is typically

provided by a utility such as vmstat so that administrators can

determine when thrashing takes place.

As mentioned about in the discussion of the clock algorithm, the kernel maintains a count of free pages with the frame table and a low-water mark to indicate when page stealing should occur. A second method that the kernel uses to try and free up frames is to send to the swap device all of the frames associated with a given process, thereby putting them on the free list. Thus, the kernel maintains a swap out thread whose job it is to evict an entire job from memory, when there is a memory shortfall.

Again, your mileage may vary, but the basic idea is for the page stealer to try and do its work and, after making a complete sweep of memory, if there is still not enough free frames, for the page stealer to wake the swap out thread. The swap out thread chooses a job (based on the size of the job and how long it has run) and goes through its entire page table. It invalidates and frees any pages that have the valid bit set, but the modified bit clear, it schedules the valid and modified pages for disk write, and it sets the execution priority of the process to zero (or takes it off the run queue entirely) for a specified period of time. The idea is to pick a large, and old process (one that has received a lot of time already) and "park" it in swap space for a while. By doing so, and freeing all of its frames, the theory goes, a bunch of smaller jobs (which are probably interactive anyway) can get in and run. Also, the free frames might relieve paging pressure so that the unswapped jobs can complete, leaving more memory for the swapped job.

After a suitable interval (OS dependent, of course) the swapped job is put back in the run queue and allowed to fault its pages back in. Sometimes it is given extra time slices as well on the theory that it does not good to let it fault its pages in only to be selected again by the swap out thread for swapping.

The solution to this problem is to rely on locality and to add a cache of page table mappings to the CPU called a translation lookaside buffer or TLB.

The TLB is usually implemented as a fast associative memory in the CPU or MMU. When the OS successfully maps a page number to a frame number it puts this mapping the TLB. The TLB is checked each time an address translation is performed and if it contains the mapping, the table look up is not performed.

Thus the true performance of the memory system depends on the size of the machine's TLB and the degree to which the workload displays spatial locality. Notice also that the TLB is per CPU. Thus when a process context switch takes place, it must typically be flushed of entries so that an new process doesn't get access to the old process' memory frames.

Secondly, notice that in the example page table memory is not paged. Thus it must be resident and there must be one for each running process. How much memory do the pages tables take up?

For example, let's imagine that we have a 64-bit address space so that a full page table is not possible. If we assume that the page size is still 512 bytes, and page table entry is 4 bytes, and there are two segments for the program (a top and bottom segment) and that we believe that largest a stack will ever get is 16 megabytes, but the test+data+heap could be 1 GB, then the sizes look like

------------------------------------------------------------- | 10 bits top level | 44 bits mid-level | 10 bits of offset | -------------------------------------------------------------How does this solve the problem? First, the top level page table contains only 1024 entries so it is not big (8 kilobytes if it encodes a page table address). Each entry of this first level page table is the address of a page table and not all of the have to be defined for the program to run. Most likely, for example, the first entry (for the text+data+heap) and the last entry (for the stack) of this page table are valid, but the other entries never get instantiated.

At the next level there are 44 bits of address space which might look like it is a problem, but actually is not if the OS defines a maximum size for test+data+heap and stack. That is, the top level entry points a page table for the text+data+heap that can be at most 44 bits in size, but could be restricted to be less (say 32 bits in size or 4GB). Similarly the last entry in the top level points to the stack's page table and it could be similarly restricted. By breaking the address space up and not full mapping the regions, you can map a very large address space without having to create a single contiguous page table.

The x86-64 architecture has several options, but the "standard" paging scheme defines a 48-bit address space, 4K byte pages and a a 4-level address decomposition:

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- | 9 bits top-level | 9 bits high-mid-level | 9 bits low-mid level | 9 bits low-level | 12 bits of offset | ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

The disadvantage is that each memory reference must access page table memory multiple times. This process of following a memory reference down through a hierarchical page table is called "walking the page table" and it is a very expensive operation. The hope is that these page table walks are made infrequent by the effectiveness of the TLB.